From Crimea and Sweden to South Dakota to Nicaragua and Costa Rica

My dear sons -

Today in the Spanish class that I’m teaching at Indiana University Northwest in Gary, Indiana, we watched a video of an interview with Rigoberta Menchú, the Nobel Peace Prize recipient from Guatemala. She talked about her family and her history as powerful motivators and catalysts for her peace work.

“Tener identidad, de dónde vienes, te ubica qué debes hacer hoy, y adónde quieres ir. Hoy, las juventudes son diversos. Son con experiencias propias. De diversos campos, diversos lugares.” -

"Having identity, knowing where you come from, tells you what you should do today, and where you want to go. Today, youth are diverse. They have their own experiences, from diverse fields, diverse places."

Paul Salopek is a journalist walking the path of human migration, out of the Horn of Africa, across the Middle East and Asia, and to the tip of South America. In his latest report in the National Geographic magazine, he hypothesizes that human civilization advanced when we were able to “remember each other’s memories,” learn from our ancestors and build on that learning. Migrating, learning, remembering.

Here are some memories from your family tree, to help you know where you are from:

South Dakota

You exist because a Swedish man (and his wife) moved to Northwest South Dakota. His granddaughter (a descendent also of a German from Crimea, Russia) married a local tenant farmer’s son, despite being the daughter of a federal judge.

You exist because an East River grocery store owner’s son, himself the son of a state representative with German roots, married a West River daughter of a by-comparison poor couple: a drinking and swearing and handsome German from Odessa, Ukraine, and a devout and enamored nurse.

My East River and West River upbringings in South Dakota

The judge’s daughter and the tenant farmer’s son were your great-grandparents, my father’s parents. The grocer’s son and nurse’s daughter were my mother’s parents. I exist because my mother and father left their small towns to study in Sioux Falls, the largest city in South Dakota, and through affinities of religion, politics, and ambition, married and stayed in the city to practice medicine and law.

Costa Rica

You exist because a migrant worker left the hot and dry plains of Guanacaste to work in the banana plantations on the Caribbean coast of Costa Rica, where he and a pretty young woman who worked at the plantation diner produced a baby, your abuelita. Her father later took the baby back to Guanacaste to live with him and wife, an otherwise childless couple. Your abuelita re-encountered her biological mother many years later, when she herself already had adolescent children.

You exist because a brave but hurting 11-year-old boy fled family upheaval in Nicaragua to live on the Pacific Coast of Costa Rica and explore his self-identified vocation of preacher in evangelical circles. Your abuelito, with his dark Nicaraguan skin and Protestant leanings, did not fit in in the whiter, Catholic Costa Rica, but he came to value the opportunities available there, nonetheless.

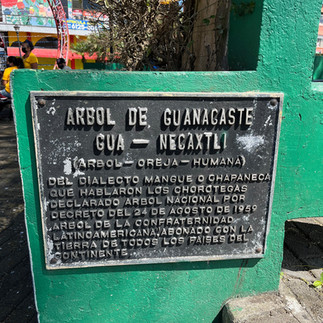

Clockwise from top left: The church where your abuelitos met and were married. With a photo of your great-grandfather. The hospital where M was born. The Guanacaste pampa, a volcano in the background. The tree that gives Guanacaste its name.

Your father exists because his mother and father found each other and believed in a vocation of Christian evangelism, personal improvement and rural development in northwestern Costa Rica and southern Nicaragua. Or your abuelito believed in this vocation, and your abuelita believed in building a Christian family with a husband who was committed to the Lord.

You, connected

And you, my loves, exist because your father and I found each other through connections of globalization, my life taking me to Latin America and his life taking him to the United States, and our whirling dance through the cyclone of cross-cultural, dual-national, bilingual relationship.

Our families’ stories became intertwined on a personal level when your father and I married, but our collective stories have been intertwined for long before then, and they continue to be. South Dakota and Costa Rica have been connected for a long time. For more than one hundred years South Dakotans have been eating bananas and drinking coffee grown in Costa Rica. Before that, Germans with our same last name, Peters, arrived to both South Dakota and to Costa Rica to farm - corn and wheat in South Dakota, coffee in Costa Rica. I’m not sure the South Dakota and Costa Rica Peters are related by blood, but we are related by history and origin-geography.

For millenia, migratory birds have been flying back and forth between North and Central America, landing in the trees above our heads, mostly unbeknownst to us. As our family and national dramas play out at eye-level, their bird’s-eye view has taken it all in, or not. They have their own dramas, their own struggles for survival.

History's circles

Your ancestors have funneled down to you, and the histories they lived seem to circle back around.

Your abuelita was born with Costa Rica’s Second Republic, in 1948. She was born on February 16, one week after the contested presidential election of Otilio Ulate Blanco. From March 12 to May 8 of that year, the country lived through its last (to-date) civil war.

You have also lived through political upheaval, contested elections, and uncertain times.

This week Russia and Ukraine have been in the news. Our ancestors, Germans who migrated to Russia (including Odessa and Crimea, places on the maps we see today of Russian troop maneuvering), played a role in the geopolitical ambitions of Catherine the Great in Russia, of the US government in the Midwest, and even now of the globalized world in Latin America. The conflicts come around again - they are not new. Remembering this history can help us to understand.

Family diversity

I love that in our family we have some of everything. Throughout the generations in our family, we have found love across boundaries - class, country, race. When we look back through the generations, we can find women with full-time jobs and PhDs, and women who have stayed home taking care of children and family. We have industrial farmers, migrant workers, bankers, pastors, lawyers, those with investments in the stock market and those without a penny to their names.

Our connections demonstrate the nature of our capitalist and globalized economy, and we can learn from those connections. And our different experiences can show us the resilience and fortitude that poverty requires, without romanticizing the difficulties of being poor. There is no one right way to be human, and all of the lives in our family that spans the continent can show us different perspectives, each important to us because they were lived by someone we love. We can learn that if we can see all people around us in love, as family members, or as relatives, as the Lakota say, we can see the importance of the experience of all people, whether they are connected to us by blood or not.

We are all connected

This writing is for you. It is my explanation to you of why you are here, and where you come from. It is also my understanding of how your life is not a disjointed collection of countries, languages, borders, passports, and bureaucracies, although it can feel that way at times. The migratory birds that live in the Midwest and in Central America do not see these two places as separate homes, any more than we would consider our living room and our bedrooms in our house different homes. They spend seasons of their lives in these different places, and belong to both. As do we. Because we are all connected, individuals that are part of a whole.

In Latin America, schoolchildren learn that there is one continent: America. This seems like a better way to envision our shared landmass. And our continent, America, is tied together by a land bridge called Central America. Costa Rica is the meeting place of the northern corn cultures of the Nahuatl, and the southern palm and tuber cultures of the Chibcha. I like that image, of a bridge, and I feel that our family is also something of a bridge, between cultures and languages, social classes and ways of life.

Rigoberta Menchú goes on to say in that interview that she believes it is important for the youth of Guatemala to know that they have potential, hope, and a future in Guatemala. That is what I hope for you both, as well. That you know that you have potential, hope and a future in Costa Rica, or the US, or where ever you decide to live in the future.

Comments