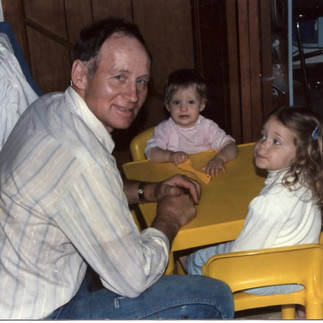

Holding one of Grandpa’s hands was always a thrill, knowing that I was holding the smooth strong hand of one of the handsomest farmers in Northeast South Dakota.

On the farm with Grandpa, 1988. Both Grandma and Grandpa Peters taught me a lot about observing my surroundings as we spent time at the farm and in their small town in South Dakota.

I really love this learning tool, because observation has so much potential for different ways of approaching it and carrying it out. Observation in the social sciences is quite structured, but it can also be approached from a very personal perspective, or even spiritually.

The idea of observation is to notice things around you. This word “notice” has been coming up in my blogging and work a lot lately. Our World Migratory Bird Day project was called “Notice, connect, find joy.” And the reflection practices that I send out every second Thursday of the month in partnership with Katrina Martich encourage us to “Notice, Connect, Practice.”

This month, Katrina invites us to notice the soil under our feet. She writes: “Take a hand trowel or sturdy spoon outside and find some bare ground. Put your hands on the ground. Feel the firmness of the soil surface, bearing the load of all we place on it. Dig a few inches into the ground and use your hands to play with the soil. Notice its colors, textures, moistness, and maybe even scent!“

Katrina’s reflections are always grounded in reality and material substances, but they have a spiritual quality too. They remind me of mindfulness practices, which invite us to pay attention in reverence to our surroundings, even minute details of our surroundings. Thich Nhat Hanh describes a walking meditation, and how paying attention to our steps, breaths, counts and half-smile can help us arrive to the present moment, as practice for observing all kinds of things in our life.

In the social sciences, we want to have structured observations that align with our research objectives, to be sure that we are looking around for relevant information that will advance our research. So we might take an observation guide to the field with us, such as the example of an observation guide provided below as a part of the following example.

Here’s the example: In the Global Perspectives course I taught at Valparaiso University, I worked with students who were planning on carrying out an observation about the items being sold at their local grocery store that were grown or made in Central America (such as coffee, pineapple, bananas, sugar, or clothing).

They prepared their observation table, while also leaving room for new discovery. Perhaps they wanted to know where the items came from, how much they cost, if the items were specialty items (such as organic or fair trade) or “conventional” items, etc. Maybe they wanted to see who was buying what product. Their research questions guided the development of the observation guide.

When systematic observation is conducted over time, with similar methods, it is called monitoring. I wrote about that in a different blog post. Monitoring allows you to see change over time, and forms the basis for new questions and learning.

Similarly, another type of observation tool could be the outdoor scavenger hunts my children receive from school. This is an example of a simple observation guide that focuses one’s attention to notice and observe things one might not automatically see.

Finally there are also other kinds of observations to be made, such as the kind of noticing one does while working on a creative writing project. In a course I took on writing, we did an exercise to practice “writing from the senses,” a kind of observation exercise. Here it is:

Sound: *Exercise: Sit in a quiet place inside or outside. Make a list of all the sounds you hear.

Taste: *Exercise: In a sentence, how would you describe the taste of a madeleine or your favorite childhood candy?

Touch: *Exercise: Right now, where you're sitting, what do you feel? Do you feel the chair pressing against your derriere? The warmth of your socks on your feet? A stray strand of hair brushing against your cheek? The tag in your shirt scratching your neck?

Smell: *Exercise: What is the worst thing you have ever smelled? How would you describe it? What is your favorite smell? How would you describe that?

Here is the assignment that I wrote for that class session, in which we were asked to write about a person using sensory information. I wrote about my Grandpa Peters:

“My Grandpa Peters always smelled of his aftershave, Skin Bracer (by Mennen) that could and can be found at any common pharmacy. So much so that after he died, we kept his bottle of this elixir. Whenever I take it out of the medicine cabinet and take in a deep breath, I am immediately transported to the farm, standing next to Grandpa at the double sink in the bathroom, or at the sink installed by the back door, watching him lather up and shave with a disposable razor. His gentleness would come through even then. I never feared he would cut himself or make a mess, and even in this intimate moment he would include us, his five granddaughters, with a smile and twinkle in his eye gleaming back from the mirror. There was also a small cup of baking soda on the sink used for brushing teeth, a fact that always sort of jostled my more urban sensibilities, which only knew brand-name industrial products like Crest or Colgate.

“Grandpa didn’t talk all that much, at least when he was around Grandma. She was the official talker of the family. But if you got him alone, say on a drive around the property or into town, he could talk the whole 12 miles there (and back) in his soft, not-too-deep of a voice. In order to spook the cows (“to see if they’re paying attention,” he would say) he would have to honk, as I’m sure that his voice could never reach the decibel level needed to wake the cows out in the middle of the pasture. But his soft-spoken-ness was never mistaken by anyone for weakness, or ignorance, or fear.

“I was always fascinated by my Grandpa’s farm hands. He was missing the tips of several of his fingers, but not to the extent that you would notice unless you were up close. His hands were thick, heavy, working hands, but always smooth and strong and gentle. Holding one of them was always a thrill, knowing that I was holding the smooth strong hand of one of the handsomest farmers in Northeast South Dakota. Those hands would gently stroke the sleeping cats that laid on his chest during his afternoon naps on the “three-season porch” that was furnished by my Grandma and adorned on high shelves with the cobalt blue glass that Grandpa collected. And those hands became vulnerable and bruised and weak as they clutched washcloths and the stuffed cat I bought for him as he lay in the hospital after his stroke, the one that eventually took him from us.”

I'm grateful for my gentle and loving Grandpa Peters.

This post in part of my series on Learning Tools, which I have honed and used in my work in study abroad and cross-cultural education both in Costa Rica and in the university classes I have taught in the US. I love using these tools in my own life, as well as in my research and activism.

Comments